|

An Interview with Seymour Menton

Founding faculty member Seymour Menton, internationally renowned expert on the Latin American novel, has donated his archive of scholarly papers to the UCI Libraries. He recently reflected on his decades as a scholar in an interview with Head of Special Collections and Archives Jackie Dooley.

JD: You came to UCI in 1965 as founding chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures. What was it like to start a new program?

SM: It was very exciting to create a program according to my own pedagogical ideas. To cite only one example, in the introductory literature courses, I had felt thwarted at Dartmouth and Kansas, which followed the usual practice of having students read short selections in a thick anthology from many authors. I was convinced that this kept students from appreciating the aesthetic, linguistic, and structural elements of a given work in its entirety. Therefore, UCI became the first American university to structure the introductory course on Latin American literature on a relatively small number of the best 20th-century short stories and novels, within the linguistic grasp of the students. The more advanced courses were devoted to theater, poetry, and particular themes in one country's literature, such as Mexico, Chile, or Argentina.

SM: It was very exciting to create a program according to my own pedagogical ideas. To cite only one example, in the introductory literature courses, I had felt thwarted at Dartmouth and Kansas, which followed the usual practice of having students read short selections in a thick anthology from many authors. I was convinced that this kept students from appreciating the aesthetic, linguistic, and structural elements of a given work in its entirety. Therefore, UCI became the first American university to structure the introductory course on Latin American literature on a relatively small number of the best 20th-century short stories and novels, within the linguistic grasp of the students. The more advanced courses were devoted to theater, poetry, and particular themes in one country's literature, such as Mexico, Chile, or Argentina.

We also immediately started looking for outstanding people to chair separate literature departments, which was difficult due to the youth of our programs, the shortage of professors in the late 1960s, and the small size of our library. People in the Humanities didn't seem to be as risk-prone as those in the sciences.

Who are some of the authors you have known over the years?

I've visited and lived in most of the Latin American countries and met many of the authors from each one. I am very proud of the letter that Julio Cortázar sent me regarding my anthology El cuento hispanoamericano. He was very impressed with my analyses of the short stories and commented that I knew the authors better than the Latin Americans themselves do.

Carlos Fuentes is the most fascinating person I've ever met. A brilliant man of tremendous culture. While visiting our home he once drew a caricature of himself and me and told me that if he hadn't been a writer, he would have liked to be a caricature artist.

Tell me about your "best-seller," El cuento hispanoamericano, which has been published in eight editions since 1964.

When I wrote to the authors for permission to include their stories, they were all delighted to be published in an anthology compiled by an American, and not one of them asked for a publication fee. Previous anthologies had made no attempt to place the stories in historical perspective, and I also included critical commentary, which no other anthology had done. With each succeeding edition, I have included new chapters with the best and most representative stories of each generation.

When I wrote to the authors for permission to include their stories, they were all delighted to be published in an anthology compiled by an American, and not one of them asked for a publication fee. Previous anthologies had made no attempt to place the stories in historical perspective, and I also included critical commentary, which no other anthology had done. With each succeeding edition, I have included new chapters with the best and most representative stories of each generation.

You write in both Spanish and English. How do you decide which to use?

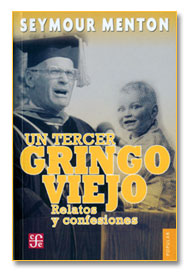

It's hard to say. In my new book of memoirs, Un tercer gringo viejo (Nov. 2005) which I call autobiographical tall tales, I wrote stories in English about growing up in New York and then translated them into Spanish. But when I wrote about events that occurred in Latin America, I wrote directly in Spanish.

Latin American fiction enjoyed its heyday in the era of magical realism, which had a major influence on other world literatures.

I consider myself fortunate that my teaching career coincided with "the boom." Borges was "discovered" in France in the 1950s, which was the beginning of it. I attended a conference in Caracas, Venezuela in 1967 that was the key moment in the emergence of the boom and generated great excitement. The conference awarded a prize for the most important Latin American novel of the previous five years, which was given to the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa. Gabriel García-Márquez's ground-breaking novel One Hundred Years of Solitude had just been published, and everyone was talking about it. I borrowed it from someone at the conference and finished reading it while standing in line at the home of Rómulo Gallegos. We had gone there to say farewell to the most outstanding criollista novelist of the period between 1920 and 1945.

Do you have a favorite Latin American author?

If I can pick only one, I would have to say García-Márquez.

What is your proudest achievement?

The totality of my career. I like to think of myself as having been influential in two areas of literature. As a literary historian, my books on the Spanish American short story, the Guatemalan novel, the Costa Rican short story, and prose fiction of the Cuban Revolution were the first of their time and still stand as the definitive works. As a literary critic, I am proud of having published the first analytical studies of several important new novels such as García Márquez's El otoño del patriarca, Carlos Fuentes's La campaña, and Abel Posse's Los perros del paraíso, as well as new interpretations of such classics as Tomás Carrasquilla's Frutos de mi tierra, Mariano Azuela's Los de abajo, and José Eustasio Rivera's La vorágine. I am also very proud of my long and varied teaching career, which began in December 1948 in Guanajuato, Mexico in a special government program to retrain rural school teachers.

|

|