The Vietnamese boat people and the land refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam were not welcomed by neighboring Asian countries. It was only through negotiations with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the United States, and other countries who agreed to accept refugees that first-asylum camps were established in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Hong Kong. The focus of these camps was on physical survival; they generally were located in remote areas and provided only the bare necessities. Crowded conditions, poor sanitation, minimal health care, and frequent violence were common, as were depression and boredom. On the other hand, camp inhabitants would organize features of a social community such as a marketplace to provide services and goods, family gardens for extra food, sport activities, and entertainment.

Refugee processing centers were another type of camp for refugees accepted for resettlement. Conditions, and therefore also the refugees' attitude, were much improved in these centers, which provided orientation and language instruction to prepare refugees for their new life in another country. The United States refugee processing centers were located in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Due to an increasing number of boat people arrivals, an international conference was held in Geneva in 1989 at which a Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) for Indochinese Refugees was formulated. It provided for a controversial screening process to separate economic refugees from those with a legitimate claim to refugee status. This conference began the process of repatriation, in which individuals are sent back to their home country if not found eligible for resettlement in another country.

Many refugee groups in the United States and other countries led an active fight against the repatriation process, citing abuse by refugee camp authorities and an unfair screening process. They contributed money and services to help people still in the camps gain refugee status. The CPA effectively ended in 1996, and from 1989 to 1996, 105,614 Vietnamese returned home (92,019 on a volunteer basis and 13,595 involuntarily). By 1996 the last of the Hmong refugees in Thai camps either returned to Laos or became part of Thailand's population, while 2,500 individuals were accepted for resettlement in the United States. Due to recent unrest in Cambodia, new refugees have made their way to the Thai border camps.

17.Rejection Letter. By Trinh Do. Painting, acrylic, 1990. Donated by Project Ngoc.

Trinh Do was labeled a dissident artist and imprisoned in Vietnam in 1988. After escaping from prison, he, his wife and ten-year old son came to Hong Kong's Whitehead Detention Center in 1989. Trinh Do painted this picture while waiting for his family's status to be determined.

18.Meeting Minutes. Council for Refugee Rights. Costa Mesa, 1990. Donated by Paul Tran.

19. Displaced Lives: Stories of Life and Culture from the Khmer Site II, Thailand. IRC Oral History Project. Bangkok: International Rescue Committee, 1990.

Site II, with its nearly 200,000 residents, was the largest of six camps for displaced Cambodians along the Thai/Cambodian border.

20.Beyond the Killing Fields. Photographs by Kari Rene Hall, text by Josh Getlin & Kari Rene Hall, edited by Marshall Lumsdell. Hong Kong: Asia 2000, 1992.

Photo essay of Site II by a Los Angeles Times Orange County photographer.

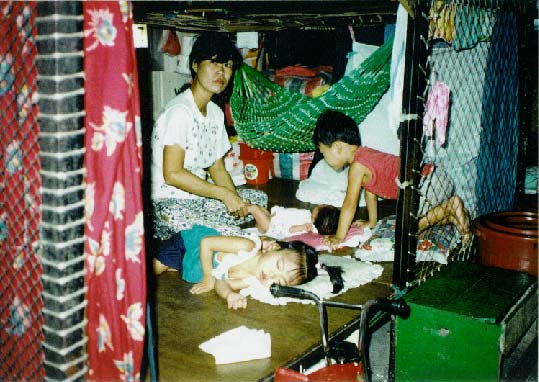

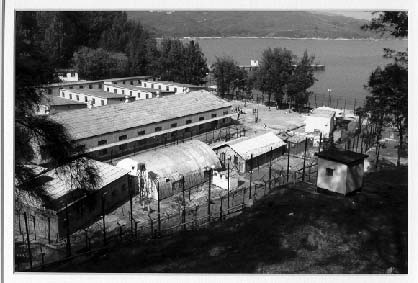

21.Photographs of refugee camps in Hong Kong. Donated by Project Ngoc.

During the 1987 Christmas break, members of the UCI student humanitarian group, Project Ngoc, made the first of several trips to the refugee camps in Hong Kong. The living space allocated for a family was an 8'x 6'x 3' cubicle, stacked three levels high, partitioned by a wooden board and draperies.

Two men

standing by cubicles inside barracks. 1988.

Family

in their cubicle. 1987.

Chi Ma

Wan Detention Centre, Hong Kong.

United Nations

High Commissioner for Refugees, 1988.

22. Letter from a woman in Dong Rek Refugee Camp in Thailand to Mr. Nhat Tien. Project Deliverance, Santa Ana, Calif., 1987? Donated by Nhat Tien.

23.Alley between row houses, Chiang Kham, Thailand. Photograph by Brigitte Marshall, 1990. Donated by Brigitte Marshall.

Chiang Kham refugee camp for Hmong and other highlander groups was located in northwestern Thailand and was much smaller than Ban Vinai. It was closed in 1993.

24. Identification cards. 1976. Donated by Guire John Cleary.

These cards belonging to a Mien family that had been in a Thai refugee camp were left at the Travelodge Transit Center in South San Francisco in 1979.

25."A visit to the Laotian refugee camp at Nong Khai, Thailand." By Mitchell I. Bonner. Typescript, 1981. Donated by Mitchell I. Bonner.

Nong Khai camp, located directly across from Vientiane, the capital city of Laos, was designated for the lowland Lao. It was closed in 1982.

26. Hmong family group, Ban Vinai. Photograph by Brigitte Marshall, 1991. Donated by Brigitte Marshall.

Ban Vinai,

at 400 acres and a capacity of 50,000 people, was one of the largest centers

for the Hmong and other highlander refugees. Located in a valley

among hills close to the Lao border, it was closed in 1992. This

picture was taken for relatives in Fresno, California, who had sent letters

and money with photographer.

|

UCI Libraries Homepage

UCI Homepage |

https://www.lib.uci.edu/ sites/all/exhibits/seaexhibit/ Copyright 1999, University of California |

UCI Southeast Asian Archive P.O. Box 19557 Irvine, CA 92623-9557 (949) 824-4968 |