The Internment of Japanese Americans during World War II

Two months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order no. 9066, allowing the U.S. Army to designate military areas where any person whom a military commander might specify, American citizen or non-citizen, could be “excluded” from society for reasons of national security. On March 2, General DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 1, informing everyone of Japanese descent that they were subject to exclusion orders from “Military Area No. 1,” essentially the entire Pacific coast. Over the next 8 months, 120,000 Japanese (two-thirds were American citizens) were ordered to leave their homes in Arizona, California, Oregon and Washington. About 90 percent of all Japanese Americans were moved to ten “detention camps” in remote locations in the nation’s interior. In contrast, and primarily for political reasons, American citizens of German and Italian ancestry were not excluded and were not classified as an “enemy race.”

The internment order was given even though there was not one documented case of espionage or treasonable activity committed by a Japanese American. Bias against those of Japanese decent had been allowed to exist long before Pearl Harbor, but their relocation to the camps strengthened such sentiments. The internees lived in temporary facilities, usually tar paper-covered barracks of simple frame construction, many without plumbing or cooking facilities. Showers and bathroom facilities were shared. The camps were often enclosed in barbed wire and surrounded by military police. Most internees stayed in the camps for the next three years. Many lost everything they owned other than what they took to the camps.

In the early 1980s, momentum grew for the idea of reparation for those who had been interned or their surviving relatives. President Bush sent a letter of apology to each former internee, followed by a redress check in 1990.

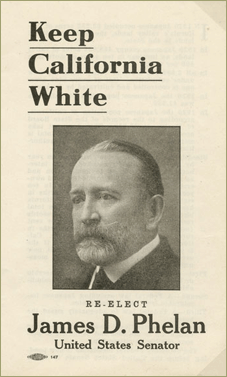

Dissenting voices in this section include white Americans Ansel Adams and Carey McWilliams, who spoke up early to question and criticize the internment even though they faced negative public reactions. We also hear internees themselves describing the situation in the camps—but in most cases, not until many years later. From the right, an early opponent of Japanese immigration and a supporter of the internment present their views.