“Books are for use” is the first law of the Five Laws of Library Science, which were proposed by S.R. Ranganathan, a mathematician and librarian from India. This section showcases scholarly publications by UCI East Asian studies faculty, as well as the UCI Libraries East Asian Collection materials that were used by scholars for their publications.

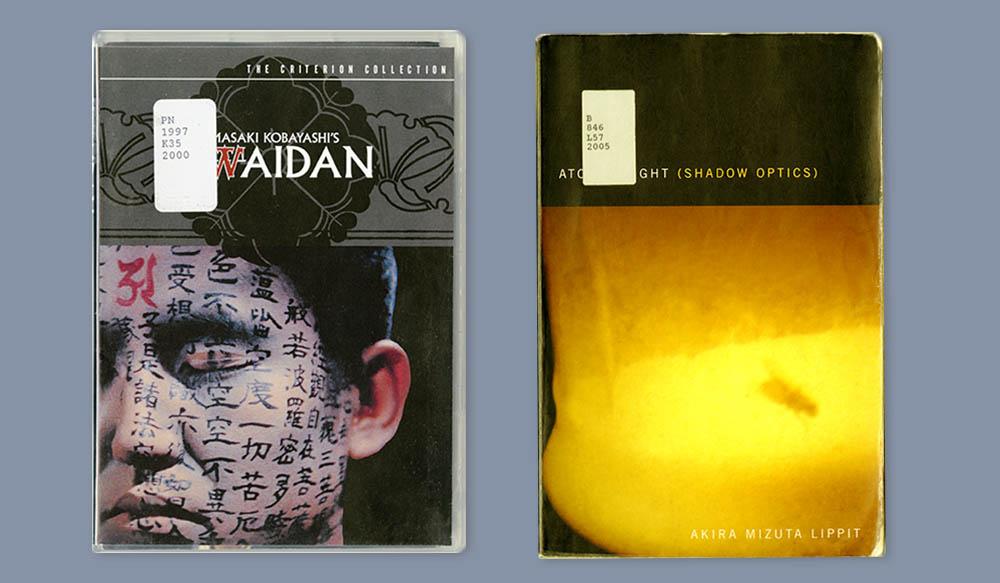

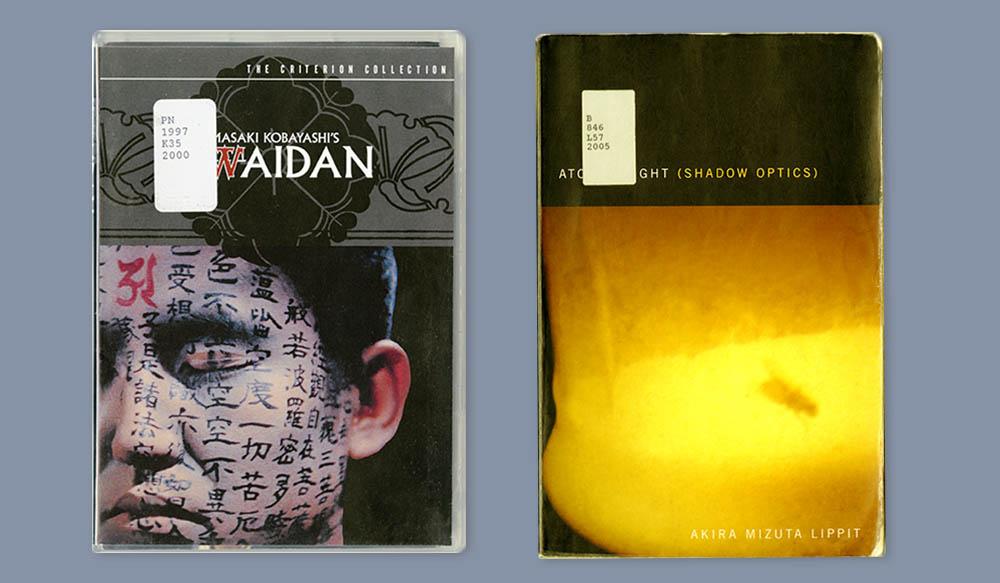

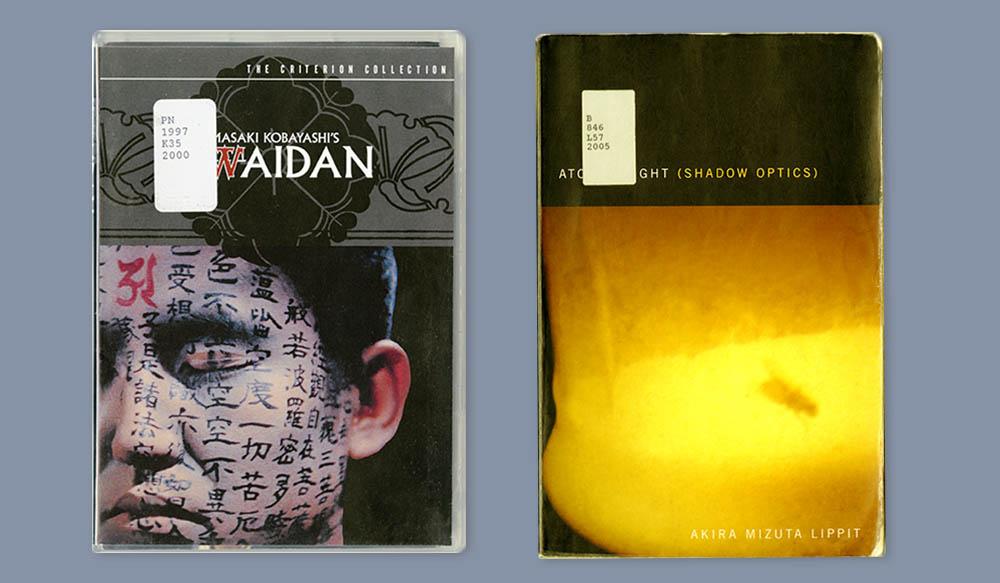

20. Japanese Film and Visual Culture Research.

a. (At left) Originally produced in 1964, this fantasy drama consists of four Japanese ghost folk tales (怪談 Kaidan or Kwaidan).

Kobayashi, Masaki. 怪談 Kwaidan. United States: Criterion Collection. 2000.

b. (At right) Films can inspire research. In his widely-cited book of visual and cultural studies, former UCI professor and chair of the Department of Film and Media Studies, Akira Mizuta Lippit uses the blind monk Hoichi’s story represented in Kobayashi’s Kwaidan film as a prelude for a discussion of the relationship between humans and the universe. Professor Akira also appreciated his “colleagues at the UCI Langson Library” for “invaluable research assistance” in the acknowledgements.

Lippit, Akira Mizuta, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2005.

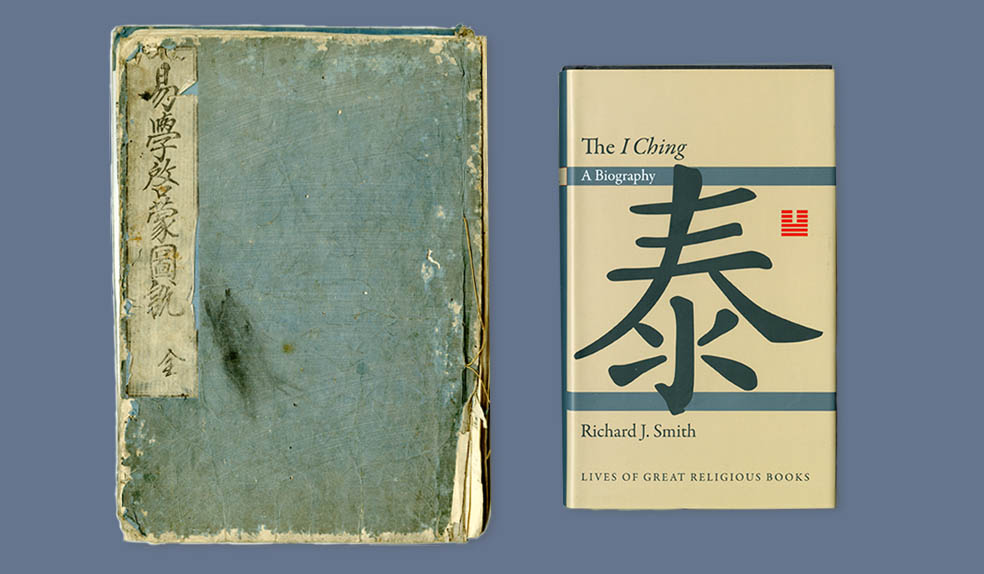

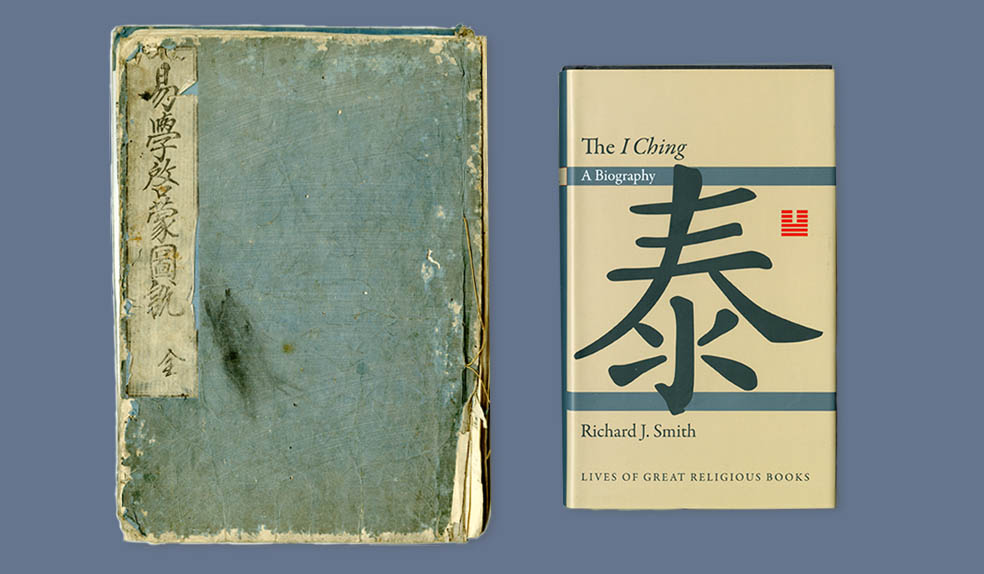

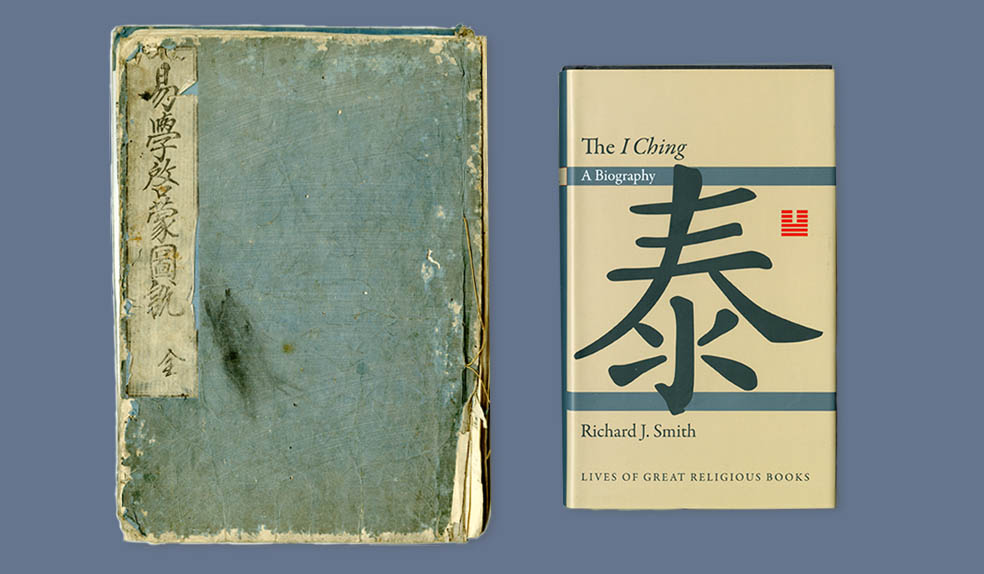

21. Classic Texts and Contemporary Research on I-Ching.

The I-Ching, also referred to as Yi-Jing or Zhou Yi (translated as “The Book of Changes” or “Classic of Changes”) is an ancient Chinese divination text, and the oldest of the Chinese classics. The I-Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

a. (At left) This 18th century illustrated woodblock book was printed in Japan, with original texts in Chinese and reading annotations in Japanese. It is one of only two copies in North America. The second copy is held at the Harvard University Library. The author, Baba Nobutake, was a medical practitioner, novelist and sinologist from Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868). Baba, Nobutake. Ekigaku Keimō Zusetsu 易學啓蒙圖說. Ōsaka: Kawachiya Yahē. 1700.

b. (At right) Old books influence modern scholarship. In The “I-Ching” a Biography, Richard J. Smith, professor emeritus at Rice University, displays two graphs on page 111 from Nobutake Baba’s Ekigaku Keimō Zusetsu (An Illustrated Introduction to I-Ching) to depict a divination table and the process of omen interpretation.

Professor Smith spent two weeks at the UCI Libraries conducting research for his book, The “I-Ching” a Biography. In this book, Smith traces I-Ching’s national and transnational travel route from within ancient China to East Asia and to the Western sphere. He also tracks the profound influence this Chinese classic work has had on the fields of philosophy, religion, art, literature, science, technology and medicine. Smith, J. Richard. The “I Ching” a Biography. California: Princeton University Press. 2012. Cover.

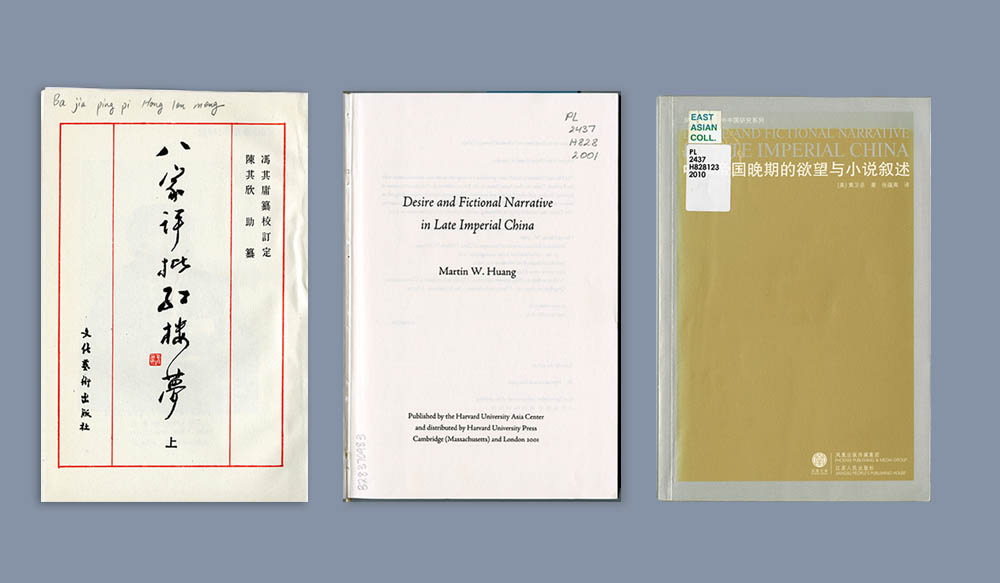

22. Classic Chinese Stories and Research.

a. (At left) Hong Lou Meng, (Dream of the Red Chamber, or the Story of the Stone) is one of China’s four great classic novels. Among its various versions is this fine edition with annotations and commentaries by eight well-established Hong Lou Meng scholars from time to time. Cao, Xueqin (author) Feng, Qiyong et al. (annotators). 八家评批红楼夢 Ba Jia Ping Pi Hong Lou Meng. Beijing: Wen hua yi shu chu ban she. 1991.

b. (At center) Originally written in English, this influential scholarly book on classic Chinese literature has been translated to Chinese. UCI’s East Asian Studies Professor Martin Huang, also a Hong Lou Meng expert, is a productive scholar. In this book, Huang used an analysis of the Chinese classic Hong Lou Meng, the commentaries edition held at the UCI Libraries, to argue that the development of the traditional Chinese fiction was closely related to Qing (affection), a fundamental desire. Huang, Martin. Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Harvard; Harvard University Asia Center. 2001.

c. (At right) Chinese translation edition of Professor Martin Huang’s Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Huang, Weizhong (author). Zhang, Yunshuang (translator). 中华帝国晚期的欲望与小说叙事 Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Nanjing. Jiangsu ren min chu ban she. 2010.

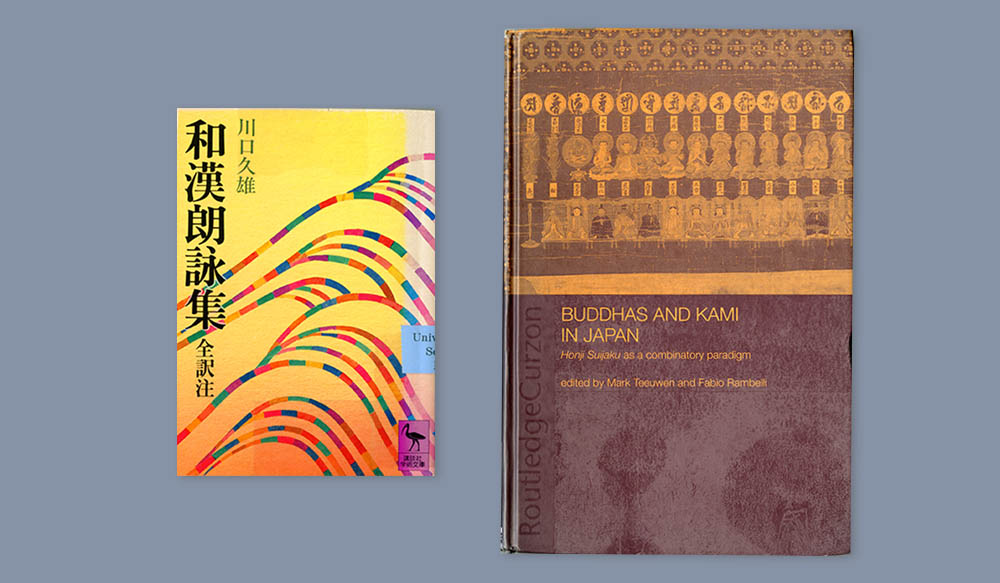

23. Japanese and Chinese Poems and Japanese Literary Culture Research.

a. (At left) Wa-kan Rōeishū Zenyakuchū (A Complete Anthology of Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing) was originally compiled and annotated by Fujiwara Kinto, a Japanese poet and court bureaucrat, of the Heian period likely in the 1st century. It was later translated and annotated in the 20th century by Japanese classic literature scholar Kawaguchi Hisao.

Kawaguchi, Hisao. Wa-kan Rōeishū Zenyakuchū 和漢朗詠集全訳注. Tōkyō: Kōdansha, 1982.

b. (At right) Ancient Chinese poems impact Japanese literature and culture studies. UCI Japanese literature Professor Susan Klein quotes Bo Juyi, the most influential ancient Chinese poet in Japan, to show the relationship between humans and Buddha in the view of the poet in his late years. The quote from Bo Juyi, translated in English by Susan Klein on page 181 of her book chapter “Wild words and syncretic deities…”, is from the original Kanji (Chinese) texts in Wa-kan Rōeishū Zenyakuchū on page 440.

Klein, Susan. Chapter “Wild words and syncretic deities: kyogen kigo and honji suijaku in medieval literary allegories.” Edited by Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli. Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. New York: RoutledgeCurzon. 2003. Page 181.

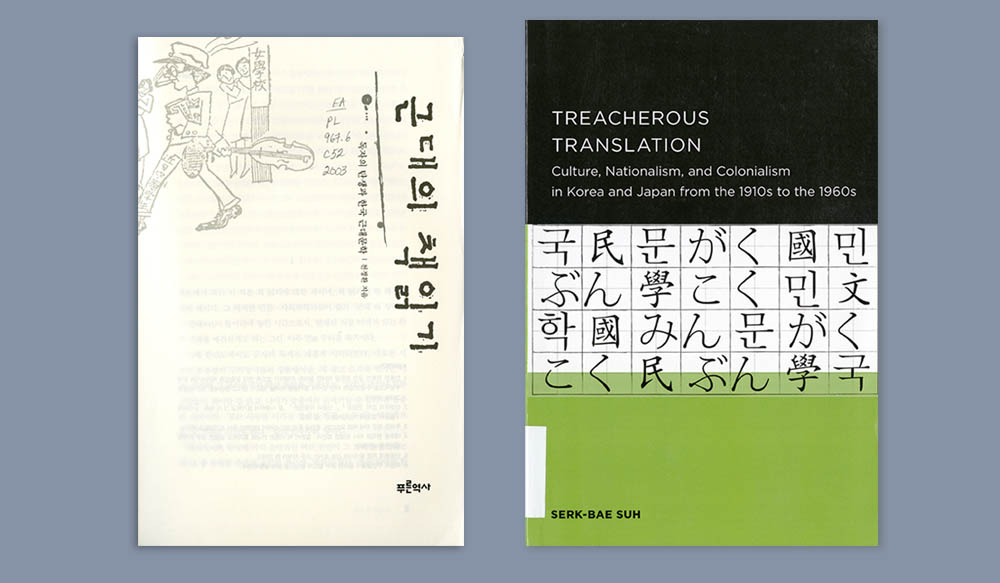

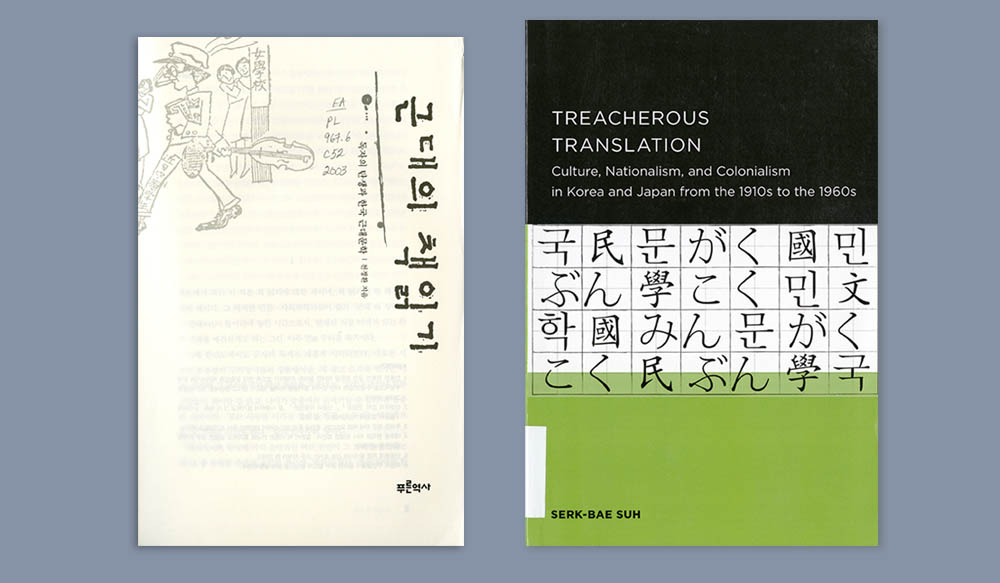

24. Modern Korean Literature and Nationalism and Colonialism Research.

a. (At left) This UCI Libraries owned book, authored by Chʻŏn, Chŏng-hwan, a Sungkyunkwan University professor, explores Korean modern literature and its readership. Chʻŏn, Chŏng-hwan. 근대의책읽기 : 독자의탄생과한국근대문학 Kŭndae ŭi Chʻaek Ilkki : Tokcha ŭi Tʻansaeng kwa Hanʼguk Kŭndae Munhak. Sŏul-si. Pʻurŭn Yŏksa. 2003. Pages 148-149.

b. (At right) Scholarly communication takes place without the limitations of language. UCI Korean literature Professor Serk-Bae Suh’s specialty is nationalism and colonialism in Korea and Japan. In this book written in the English language, Professor Suh “examines the role of translation — the rendering of texts and ideas from one language to another, as both act and trope — in shaping attitudes toward nationalism and colonialism in Korean and Japanese intellectual discourse between the time of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910 and the passing of the colonial generation in the mid-1960s.”

Professor Suh cites pages 148-149 of Chʻŏn’s work Kŭndae ŭi chʻaek ilkki. These two pages explore how the Korean people kept their own writing tradition even though the Japanese imposed strict school education policies during the colonial period.

Suh, Serk-Bae. Treacherous Translation: Culture, Nationalism, and Colonialism in Korea and Japan from the 1910s to the 1960s. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2013. Pages 152 and 195.

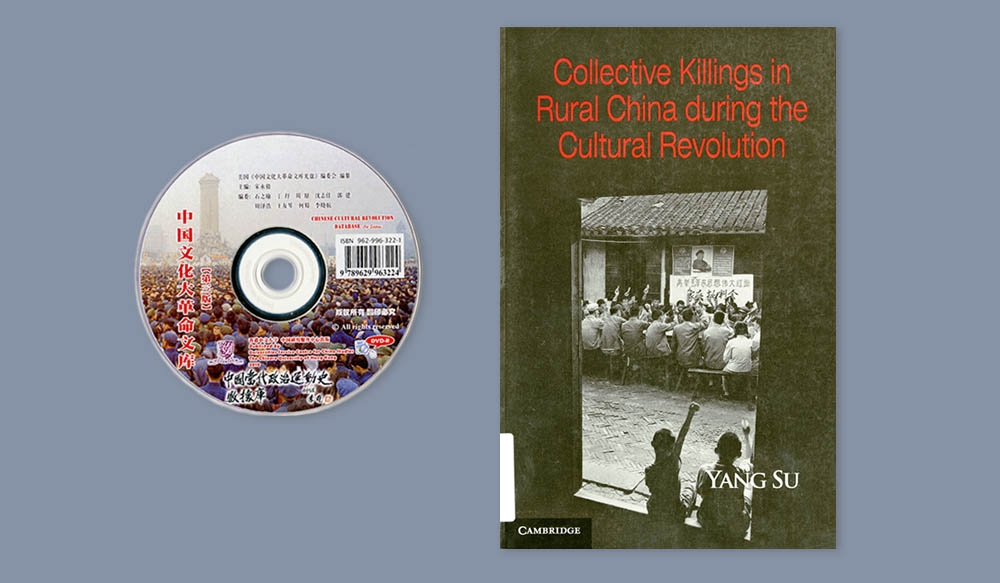

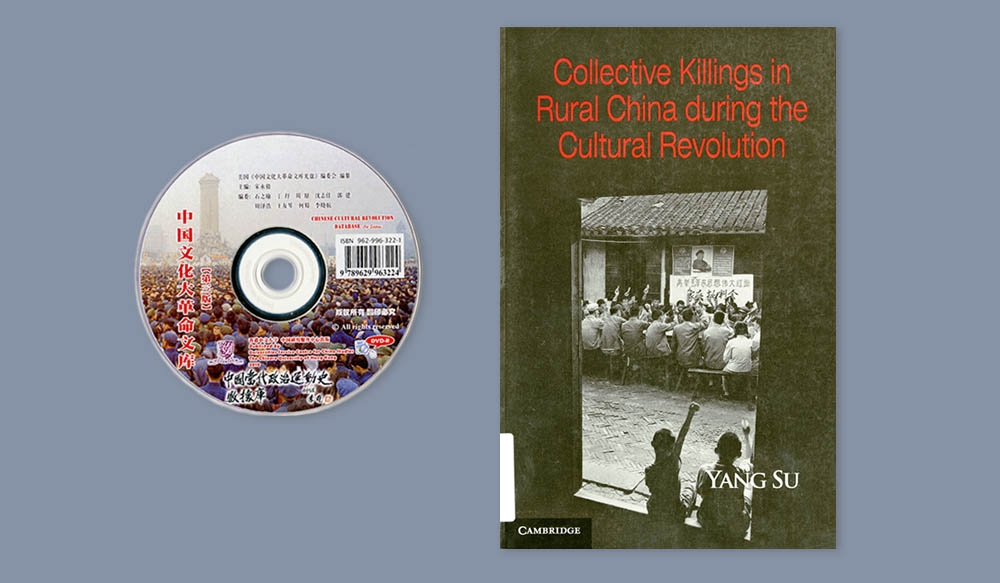

25. Chinese Databases and Research on the Cultural Revolution.

a. (At left) This standalone database contains original documents related to the Chinese Cultural Revolution including China’s Communist Party notices, instructions, proclamations, speeches and major media commentaries with detailed citations.

Song, Yongyi. 中国文化大革命文库 Zhongguo Wen Hua Da Ge Ming Wen Ku (Chinese Cultural Revolution database), 3rd edition. Xianggang: Xianggang zhong wen da xue Zhongguo yan jiu fu wu zhong xin. 2010.

b. (At right) Primary sources are essential to historical context analysis. This well-received book by UCI Sociology Professor Yang Su cites a Chinese government document released in 1978, two years after the ending of the Cultural Revolution, as a background on how official numbers of collective killings surfaced. The Chinese government document, as noted by Professor Su, was retrieved from Zhongguo Wen Hua Da Ge Ming Wen Ku (Chinese Cultural Revolution database).

Su, Yang. Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2011. Page 42.

26. Chinese Journal Articles and Research on Social Assistance in Contemporary China.

a. (At left) Retrieved from China Academic Journals, in the UCI Libraries database subscription, this article published in the core Chinese journal documents China’s major shift in the 1990s from employee welfare to social security.

Ding, Langfu. “从单位福利到社会保障-记中国城市居民最低生活保障制度 (From unit welfare to social security — recording the emergence of Chinese urban residents’ minimum livelihood guarantee system)”. 中国民政 (China Civil Affairs). Number 11. 1999. Pages 6-7.

b. (At right) Electronic resources make scholarly activities more efficient. Recently retired political science Professor Emeritus Dorie Solinger, frequently uses the UCI Libraries online journal and statistical databases for her research. In this article on China’s welfare development published in the flagship journal in the area of Asian studies, Professor Solinger cited Ding’s article to support her statement on the Chinese government’s effort of establishing the Minimum Livelihood Guarantee scheme to enforce social stability.

Solinger, Dorothy. “Three welfare models and current Chinese social assistance: Confucian justifications, variable applications.” Journal of Asian Studies. Volume 74, Number 4. November 1, 2015. Pages 977-999.

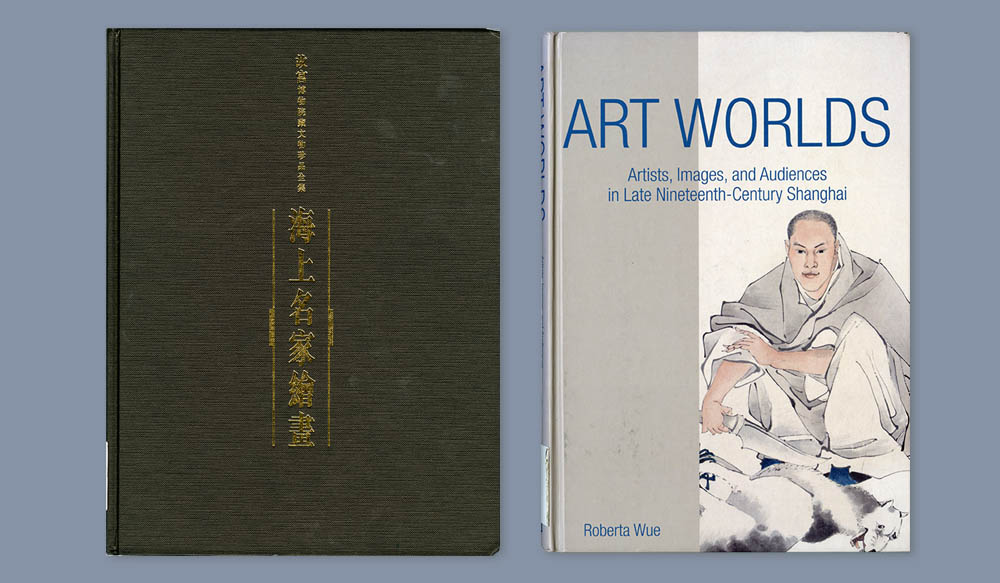

27. Art Books and Art History Research.

a. (At left) This book, published under the series title 故宮博物院藏文物珍品全集 (Complete Collection of the Treasures in the Palace Museum), features paintings by many master artists in the Shanghai region.

Pan, Shenliang (ed.) 海上名家绘画 Hai Shang Ming Jia Hui Hua. Xianggang. Shang wu yin shu guan. 1997.

b. (At right) Art books with alluring images are essential to art history research. UCI Art History Professor Roberta Wue examines how natural elements like bamboo and rock in a painting symbolize a scholar’s resilience. To make this assertion, Professor Wu uses sample paintings from Pan’s edited book Hai Shang Ming Jia Hui Hua as visual demonstration, including “Withered tree, bamboo and rock” on page 137. It was created by Gao Yong, 高邕, a modern Chinese artist from Shanghai who lived from 1850 to 1921.

Wue, Roberta. Art Worlds: Artists, Images, and Audiences in Late Nineteenth-Century Shanghai. Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press. 2014. Page 34.

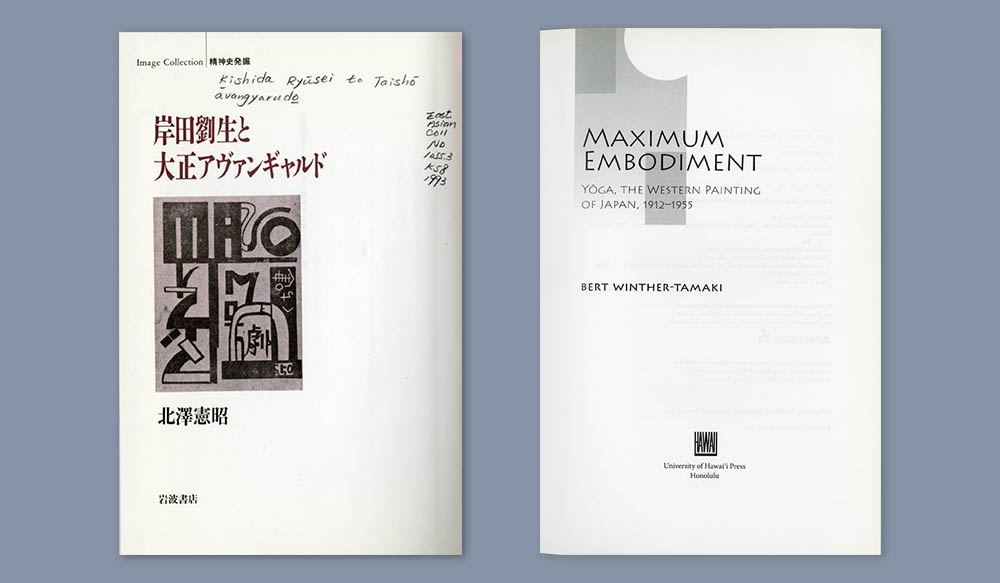

28. Japanese Artists and Western Painting in Modern Japan.

a. (At left) A book about Kishida Ryūsei 岸田劉生, a Japanese artist in the Taishō and Shōwa period (1912-1989) who is best known for his realistic Western or yoga-style portraiture.

Kitazawa, Noriaki. 岸田劉生と大正アヴァンギャルド Kishida Ryūsei to Taishō Avangyarudo. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. 1993. Cover.

b. (At right) Art is universal and reciprocal. Professor Bert Winther-Tamaki, a UCI Japanese art history professor and the department chair of Art History, specializes in researching the history of interactions between Japanese and American art worlds. On page 33 of this book, Professor Winther-Tamaki discusses Taishō and Shōwa period artist Kinshida Ryūsei’s earlier experience with God in his portraits and self-portraits. In his book, Winther-Tamaki cites page 27 of Kitazawa’s Kishida Ryūsei to Taishō Avangyarudo. On page 32, Winther-Tamaki also explores two self-portraits painted by Kishida just one month apart.

Winther-Tamaki, Bert. Maximum Embodiment : Yōga, the Western Painting of Japan, 1912-1955. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. 2012.

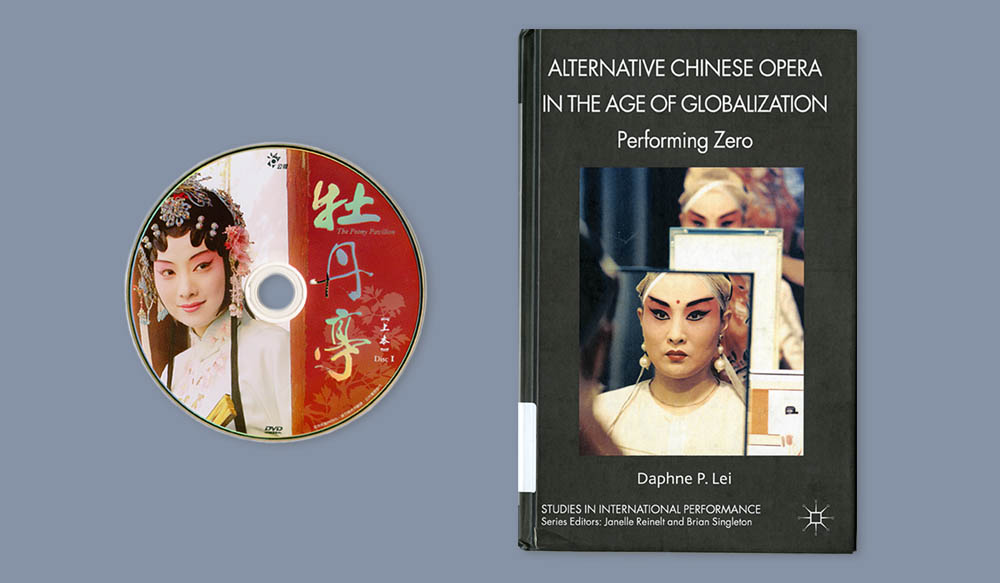

29. Chinese Opera Performance and Research.

a. (At left) Mu Dan Ting (The Peony Pavilion), is a romantic tragicomedy play written in 1598 by Tang Xianzu, a famous Chinese playwright of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The play has been regarded as China’s Romeo and Juliet. This edition of Kunqu, one of the oldest surviving forms of Chinese opera, was revised and edited by Bai Xianyong, a renowned writer and critic from Taiwan, and directed by Wang Shiyu, a master Kunqu performer.

Tang, Xianzu and Bai, Xianyong. 牡丹亭 (Mu Dan Ting). Taibei: Gong gong dian shi. Production Company. 2004.

b. (At right) Internationally recognized for her scholarship on Chinese opera, Asian American theatre, intercultural, diasporic and transnational, and transpacific performance, UCI Professor of Drama Daphne Lei cites the UCI Libraries’ DVD copy of the youth edition of Mu Dan Ting in the beginning of and throughout Chapter 3 of the book The Blossoming of the Transnational Peony: Performing Alternative China in California.

Lei, Daphne. Alternative Chinese Opera in the Age of Globalization: Performing Zero. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2011.

20. Japanese Film and Visual Culture Research.

a. (At left) Originally produced in 1964, this fantasy drama consists of four Japanese ghost folk tales (怪談 Kaidan or Kwaidan).

Kobayashi, Masaki. 怪談 Kwaidan. United States: Criterion Collection. 2000.

b. (At right) Films can inspire research. In his widely-cited book of visual and cultural studies, former UCI professor and chair of the Department of Film and Media Studies, Akira Mizuta Lippit uses the blind monk Hoichi’s story represented in Kobayashi’s Kwaidan film as a prelude for a discussion of the relationship between humans and the universe. Professor Akira also appreciated his “colleagues at the UCI Langson Library” for “invaluable research assistance” in the acknowledgements.

Lippit, Akira Mizuta, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2005.

21. Classic Texts and Contemporary Research on I-Ching.

The I-Ching, also referred to as Yi-Jing or Zhou Yi (translated as “The Book of Changes” or “Classic of Changes”) is an ancient Chinese divination text, and the oldest of the Chinese classics. The I-Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

a. (At left) This 18th century illustrated woodblock book was printed in Japan, with original texts in Chinese and reading annotations in Japanese. It is one of only two copies in North America. The second copy is held at the Harvard University Library. The author, Baba Nobutake, was a medical practitioner, novelist and sinologist from Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868). Baba, Nobutake. Ekigaku Keimō Zusetsu 易學啓蒙圖說. Ōsaka: Kawachiya Yahē. 1700.

b. (At right) Old books influence modern scholarship. In The “I-Ching” a Biography, Richard J. Smith, professor emeritus at Rice University, displays two graphs on page 111 from Nobutake Baba’s Ekigaku Keimō Zusetsu (An Illustrated Introduction to I-Ching) to depict a divination table and the process of omen interpretation.

Professor Smith spent two weeks at the UCI Libraries conducting research for his book, The“I-Ching” a Biography. In this book, Smith traces I-Ching’s national and transnational travel route from within ancient China to East Asia and to the Western sphere. He also tracks the profound influence this Chinese classic work has had on the fields of philosophy, religion, art, literature, science, technology and medicine. Smith, J. Richard. The “I Ching” a Biography. California: Princeton University Press. 2012. Cover.

22. Classic Chinese Stories and Research.

a. (At left) Hong Lou Meng, (Dream of the Red Chamber, or the Story of the Stone) is one of China’s four great classic novels. Among its various versions is this fine edition with annotations and commentaries by eight well-established Hong Lou Meng scholars from time to time. Cao, Xueqin (author) Feng, Qiyong et al. (annotators). 八家评批红楼夢 Ba Jia Ping Pi Hong Lou Meng. Beijing: Wen hua yi shu chu ban she. 1991.

b. (At center) Originally written in English, this influential scholarly book on classic Chinese literature has been translated to Chinese. UCI’s East Asian Studies Professor Martin Huang, also a Hong Lou Meng expert, is a productive scholar. In this book, Huang used an analysis of the Chinese classic Hong Lou Meng, the commentaries edition held at the UCI Libraries, to argue that the development of the traditional Chinese fiction was closely related to Qing (affection), a fundamental desire. Huang, Martin. Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Harvard; Harvard University Asia Center. 2001.

c. (At right) Chinese translation edition of Professor Martin Huang’s Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Huang, Weizhong (author). Zhang, Yunshuang (translator). 中华帝国晚期的欲望与小说叙事 Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Nanjing. Jiangsu ren min chu ban she. 2010.

23. Japanese and Chinese Poems and Japanese Literary Culture Research.

a. (At left) Wa-kan Rōeishū Zenyakuchū (A Complete Anthology of Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing) was originally compiled and annotated by Fujiwara Kinto, a Japanese poet and court bureaucrat, of the Heian period likely in the 1st century. It was later translated and annotated in the 20th century by Japanese classic literature scholar Kawaguchi Hisao.

Kawaguchi, Hisao. Wa-kan Rōeishū Zenyakuchū 和漢朗詠集全訳注. Tōkyō: Kōdansha, 1982.

b. (At right) Ancient Chinese poems impact Japanese literature and culture studies. UCI Japanese literature Professor Susan Klein quotes Bo Juyi, the most influential ancient Chinese poet in Japan, to show the relationship between humans and Buddha in the view of the poet in his late years. The quote from Bo Juyi, translated in English by Susan Klein on page 181 of her book chapter “Wild words and syncretic deities…”, is from the original Kanji (Chinese) texts in Wa-kan RōeishūZenyakuchū on page 440.

Klein, Susan. Chapter “Wild words and syncretic deities: kyogen kigo and honji suijaku in medieval literary allegories.” Edited by Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli. Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. New York: RoutledgeCurzon. 2003. Page 181.

24. Modern Korean Literature and Nationalism and Colonialism Research.

a. (At left) This UCI Libraries owned book, authored by Chʻŏn, Chŏng-hwan, a Sungkyunkwan University professor, explores Korean modern literature and its readership. Chʻŏn, Chŏng-hwan. 근대의책읽기 : 독자의탄생과한국근대문학 Kŭndae ŭi Chʻaek Ilkki : Tokcha ŭi Tʻansaeng kwa Hanʼguk Kŭndae Munhak. Sŏul-si. Pʻurŭn Yŏksa. 2003. Pages 148-149.

b. (At right) Scholarly communication takes place without the limitations of language. UCI Korean literature Professor Serk-Bae Suh’s specialty is nationalism and colonialism in Korea and Japan. In this book written in the English language, Professor Suh “examines the role of translation — the rendering of texts and ideas from one language to another, as both act and trope — in shaping attitudes toward nationalism and colonialism in Korean and Japanese intellectual discourse between the time of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910 and the passing of the colonial generation in the mid-1960s.”

Professor Suh cites pages 148-149 of Chʻŏn’s work Kŭndae ŭi chʻaek ilkki. These two pages explore how the Korean people kept their own writing tradition even though the Japanese imposed strict school education policies during the colonial period.

Suh, Serk-Bae. Treacherous Translation: Culture, Nationalism, and Colonialism in Korea and Japan from the 1910s to the 1960s. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2013. Pages 152 and 195.

25. Chinese Databases and Research on the Cultural Revolution.

a. (At left) This standalone database contains original documents related to the Chinese Cultural Revolution including China’s Communist Party notices, instructions, proclamations, speeches and major media commentaries with detailed citations.

Song, Yongyi. 中国文化大革命文库 Zhongguo Wen Hua Da Ge Ming Wen Ku (Chinese Cultural Revolution database), 3rd edition. Xianggang: Xianggang zhong wen da xue Zhongguo yan jiu fu wu zhong xin. 2010.

b. (At right) Primary sources are essential to historical context analysis. This well-received book by UCI Sociology Professor Yang Su cites a Chinese government document released in 1978, two years after the ending of the Cultural Revolution, as a background on how official numbers of collective killings surfaced. The Chinese government document, as noted by Professor Su, was retrieved from Zhongguo Wen Hua Da Ge Ming Wen Ku (Chinese Cultural Revolution database).

Su, Yang. Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2011. Page 42.

26. Chinese Journal Articles and Research on Social Assistance in Contemporary China.

a. (At left) Retrieved from China Academic Journals, in the UCI Libraries database subscription, this article published in the core Chinese journal documents China’s major shift in the 1990s from employee welfare to social security.

Ding, Langfu. “从单位福利到社会保障-记中国城市居民最低生活保障制度 (From unit welfare to social security — recording the emergence of Chinese urban residents’ minimum livelihood guarantee system)”. 中国民政 (China Civil Affairs). Number 11. 1999. Pages 6-7.

b. (At right) Electronic resources make scholarly activities more efficient. Recently retired political science Professor Emeritus Dorie Solinger, frequently uses the UCI Libraries online journal and statistical databases for her research. In this article on China’s welfare development published in the flagship journal in the area of Asian studies, Professor Solinger cited Ding’s article to support her statement on the Chinese government’s effort of establishing the Minimum Livelihood Guarantee scheme to enforce social stability.

Solinger, Dorothy. “Three welfare models and current Chinese social assistance: Confucian justifications, variable applications.” Journal of Asian Studies. Volume 74, Number 4. November 1, 2015. Pages 977-999.

27. Art Books and Art History Research.

a. (At left) This book, published under the series title 故宮博物院藏文物珍品全集 (Complete Collection of the Treasures in the Palace Museum), features paintings by many master artists in the Shanghai region.

Pan, Shenliang (ed.) 海上名家绘画 Hai Shang Ming Jia Hui Hua. Xianggang. Shang wu yin shu guan. 1997.

b. (At right) Art books with alluring images are essential to art history research. UCI Art History Professor Roberta Wue examines how natural elements like bamboo and rock in a painting symbolize a scholar’s resilience. To make this assertion, Professor Wu uses sample paintings from Pan’s edited book Hai Shang Ming Jia Hui Hua as visual demonstration, including “Withered tree, bamboo and rock” on page 137. It was created by Gao Yong, 高邕, a modern Chinese artist from Shanghai who lived from 1850 to 1921.

Wue, Roberta. Art Worlds: Artists, Images, and Audiences in Late Nineteenth-Century Shanghai. Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press. 2014. Page 34.

28. Japanese Artists and Western Painting in Modern Japan.

a. (At left) A book about Kishida Ryūsei 岸田劉生, a Japanese artist in the Taishō and Shōwa period (1912-1989) who is best known for his realistic Western or yoga-style portraiture.

Kitazawa, Noriaki. 岸田劉生と大正アヴァンギャルド Kishida Ryūsei to Taishō Avangyarudo. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. 1993. Cover.

b. (At right) Art is universal and reciprocal. Professor Bert Winther-Tamaki, a UCI Japanese art history professor and the department chair of Art History, specializes in researching the history of interactions between Japanese and American art worlds. On page 33 of this book, Professor Winther-Tamaki discusses Taishō and Shōwa period artist Kinshida Ryūsei’s earlier experience with God in his portraits and self-portraits. In his book, Winther-Tamaki cites page 27 of Kitazawa’s Kishida Ryūsei to Taishō Avangyarudo. On page 32, Winther-Tamaki also explores two self-portraits painted by Kishida just one month apart.

Winther-Tamaki, Bert. Maximum Embodiment : Yōga, the Western Painting of Japan, 1912-1955. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. 2012.

29. Chinese Opera Performance and Research.

a. (At left) Mu Dan Ting (The Peony Pavilion), is a romantic tragicomedy play written in 1598 by Tang Xianzu, a famous Chinese playwright of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The play has been regarded as China’s Romeo and Juliet. This edition of Kunqu, one of the oldest surviving forms of Chinese opera, was revised and edited by Bai Xianyong, a renowned writer and critic from Taiwan, and directed by Wang Shiyu, a master Kunqu performer.

Tang, Xianzu and Bai, Xianyong. 牡丹亭 (Mu Dan Ting). Taibei: Gong gong dian shi. Production Company. 2004.

b. (At right) Internationally recognized for her scholarship on Chinese opera, Asian American theatre, intercultural, diasporic and transnational, and transpacific performance, UCI Professor of Drama Daphne Lei cites the UCI Libraries’ DVD copy of the youth edition of Mu Dan Ting in the beginning of and throughout Chapter 3 of the book The Blossoming of the Transnational Peony: Performing Alternative China in California.

Lei, Daphne. Alternative Chinese Opera in the Age of Globalization: Performing Zero. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2011.

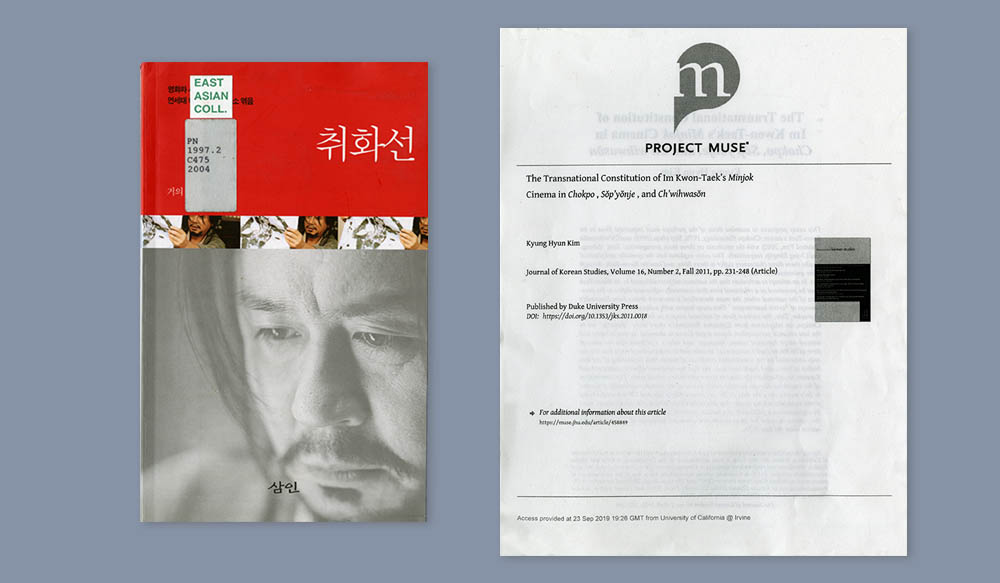

30. Korean Film Directors and Research on Korean Nationalist Cinema.

a. (At left) This book contains interview transcripts between Im Kwon-Taek, a renowned Korean film director, and Chŏng Sŏngil, a Korean film critic.

Kim Soyŏng. “Ch’wihwasŏnkwa hankuk yŏnghwasa.” Yŏnsedae Midiŏ Atʻ̆ū Yŏnʼguso. Chʻwihwasŏn 취화선. Sŏul-si: Samin. 2004. Pages 13-31.

b. (At right) Interviews as primary sources are extremely valuable to research. UCI Korean literature and film Professor Kyung Hyun Kim references on page 234 of his article an interview between Im Kwon-Taek and Chŏng Sŏngil. The interview transcripts between Im Kwon-Taek and Chŏng Sŏngil are quoted in Kim Soyŏng’s book chapter about film Chʻwihwasŏn on page 26 and page 27. The interview details the discussion of Im’s “hybrid identity” from a former mugukchŏk (no-national-identity) film director to a minjok (nationalism) film director.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. The transnational constitution of Im Kwon-Taek’s Minjok cinema in Chokpo, Sŏpʼyŏnje, and Chʼwihwasŏn. Journal of Korean Studies. Volume 16. Number 2. Fall 2011. Pages 231-248.

31. UCI East Asian Studies Faculty and Academic Units.

a. UCI East Asian Studies academic units and centers (logos) and affiliated faculty (on linked pages)

i. UCI Department of East Asian Studies School for Humanities

ii. UCI Center for Asian Studies

iii. UCI Center for Critical Korean Studies School for Humanities

iv. UCI Long U.S.-China Institute.

Courtesy of the University of California, Irvine.

b. Click here for additional selective publications by core East Asian Studies faculty members. Courtesy of the University of California, Irvine.

Introduction - Birth and Growth (Items 1-12) - Rare and Precious Resources (Items 13-19)

Books are for Use (Items 20-31) - Resources for the Local Community (Items 32-41) - Grants and Gifts (Items 42-49)

Working with Global Partners to Build the Collection (Items 50-56) - With the Help of Faculty and Friends (Items 57-62)

Autographed Books and Tributes (Items 63-72)

Questions? Please contact us at partners@uci.edu. Copyright Statement.